Signed Git Commits

Proving that you made git commits is useful. This article walks you through the steps needed to enable this behaviour.

When you sign a Git commit you can prove that it was definitely you that made the commit (assuming you look after your keys and passwords sensibly!) and that the code change is really what you wrote.

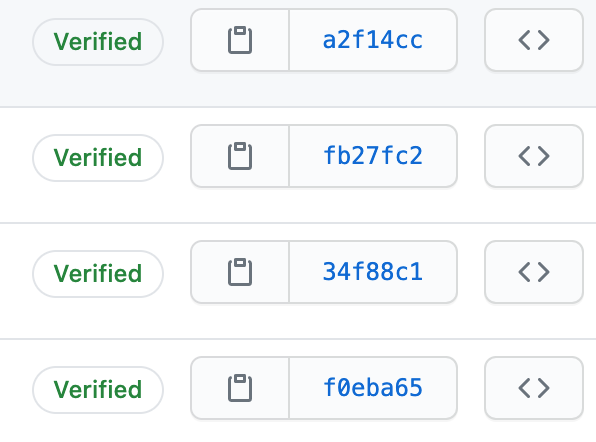

Also, don’t you just like the warm glow of the “Verified” label next to your commits?

- this unordered seed list will be replaced by the toc

Configuring Signed Commits

Locating your key

Creating, and managing your key is a separate conversation. We’ll assume you’ve already created your key.

❯ gpg --list-secret-keys --keyid-format LONG |grep sec

sec dsa1024/8788FBC53885BB11 2005-05-17 [SC] [expires: 2030-04-19]

In this example, the value you want to use later is 8788FBC53885BB11.

Obviously you’ll have, and use, a different value here.

Make the value easier to reference later by adding this to your ${SHELL}-rc

file:

export GIT_SIGNINGKEY_ID="8788FBC53885BB11"

Configuring gpg-agent

gpg-agent is a necessary part of the process. It’s possible to have

gpg-agent take on the role of ssh-agent but this didn’t behave well when we

tried it, so it’s better to configure ssh-agent

as you would normally, then configure gpg-agent by adding the following to

your ${SHELL}-rc file:

if type "gpg-agent" >/dev/null; then

# if it looks like it's already running, don't bother

# starting the agent

# it looks like we can have the magic files in more than one place:

# - ~/.gnupg/

# - $GNUPGHOME

# - /run/user/{ID}/gnupg/

if [ -z "${GNUPGHOME}" ] && [ -d "/run/user/$(id -u)/gnupg" ]; then

export GNUPGHOME="/run/user/$(id -u)/gnupg"

fi

if [ ! -e "${GNUPGHOME:-$HOME/.gnupg}/S.gpg-agent" ]; then

gpg-agent --daemon

fi

# p10k does strange things with `tty`, so we play it safe

# we do have the agent, so we always want to set this in a new session

export GPG_TTY=$(tty)

if [ "${GPG_TTY}" = "not a tty" ]; then

if [ -n "${TTY}" ]; then

export GPG_TTY="${TTY}"

else

echo "something went wrong with `tty` in $(basename $0) run this: "

echo ' export GPG_TTY=$(tty)'

fi

fi

fi

Configuring Git To Use The Key

Add the following to your ${SHELL}-rc file, after the export statement in

the earlier step.

# it's nice to sign your commits

# we'll only set these if it looks likes the user wants us to

# (by them setting a variable we just made up for them)

if [ -n "${GIT_SIGNINGKEY_ID}" ]; then

# git commit signing

# https://gist.github.com/webframp/75c680930b6b2caba9a1be6ec23477c1

# both gitlab and github seem to not like push.gpgsign, so we ensure that's

# explicitly set to false

git config --global gpg.program gpg

git config --global user.signingkey "${GIT_SIGNINGKEY_ID}"

git config --global commit.gpgsign true

git config --global push.gpgsign false

fi

You can add this directly to your ~/.gitconfig file, but we prefer to have as

much behaviour as possible in re-runnable snippets. (see

“shellrc.d” below for details)

Commit!

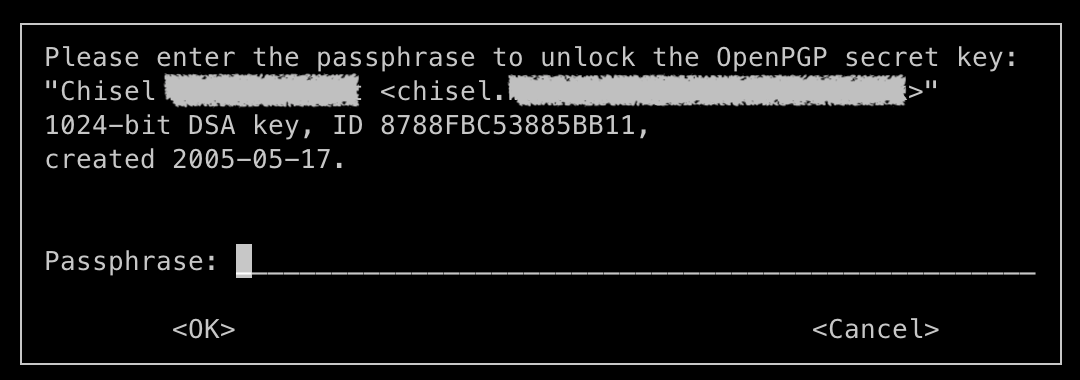

At this point you should see slightly different behaviour locally when you commit.

After completing the commit message, you’ll be prompted for your GPG password:

Don’t panic! gpg-agent caches this for a few minutes, so you don’t have to

enter this for every commit! This is a blessing when youre performing an

interactive rebase on your working branch.

Add your key to github/gitlab

One step that’s easy to forget after you’ve wrangled everything into submission locally is to upload your GPG public key to your Github/Gitlab account.

Without this you won’t get the “Verified” label to show for all your effort.

shellrc.d

Of course, this is all easy enough to paste into one huge ${SHELL}-rc file,

but we recommend that you take a look at a different, and portable, way to

manage your shell configuration.

Check out shellrd.c, then have a look at the specific files in our extended configuration:

The git configuration is in two parts: